Self-Interview in The Nervous Breakdown

This interview was published in The Nervous Breakdown on January 15, 2013. I bumped into it again while migrating content from the old wordweeds website. Enjoy!

You’ve been awfully quiet today. What’s up?

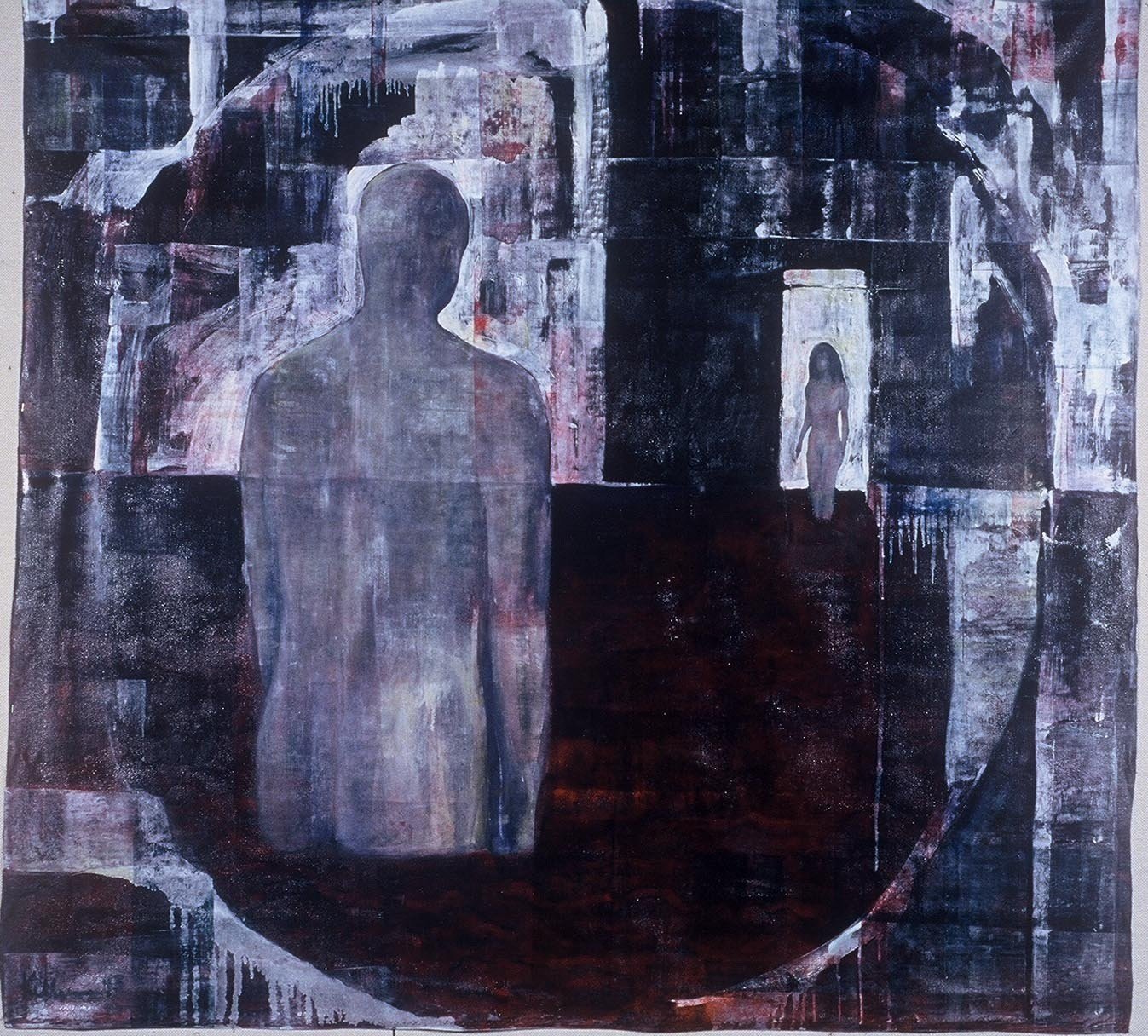

I’ve been thinking of my attraction to bardo spaces. The in-between places. I suppose I’ve been dancing there since my early 20s when I left organized religion and began formally pursuing the visual and literary arts. An early exhibit of oils and monotypes called Between featured quasi-mythological, autobiographical figures knee-deep to chest-high in water, both on land and at sea at once. Looking back, it isn’t a surprise that ten years later I would begin seriously studying Tibetan Buddhism where this concept of the between figures prominently. It’s a natural fit for me. Any philosophy that makes a practice out of living beyond duality and with the concept of both/and feels like home.

-

After all this time would you say this philosophy still informs your aesthetic sensibility?

Yes, probably more than anything else.

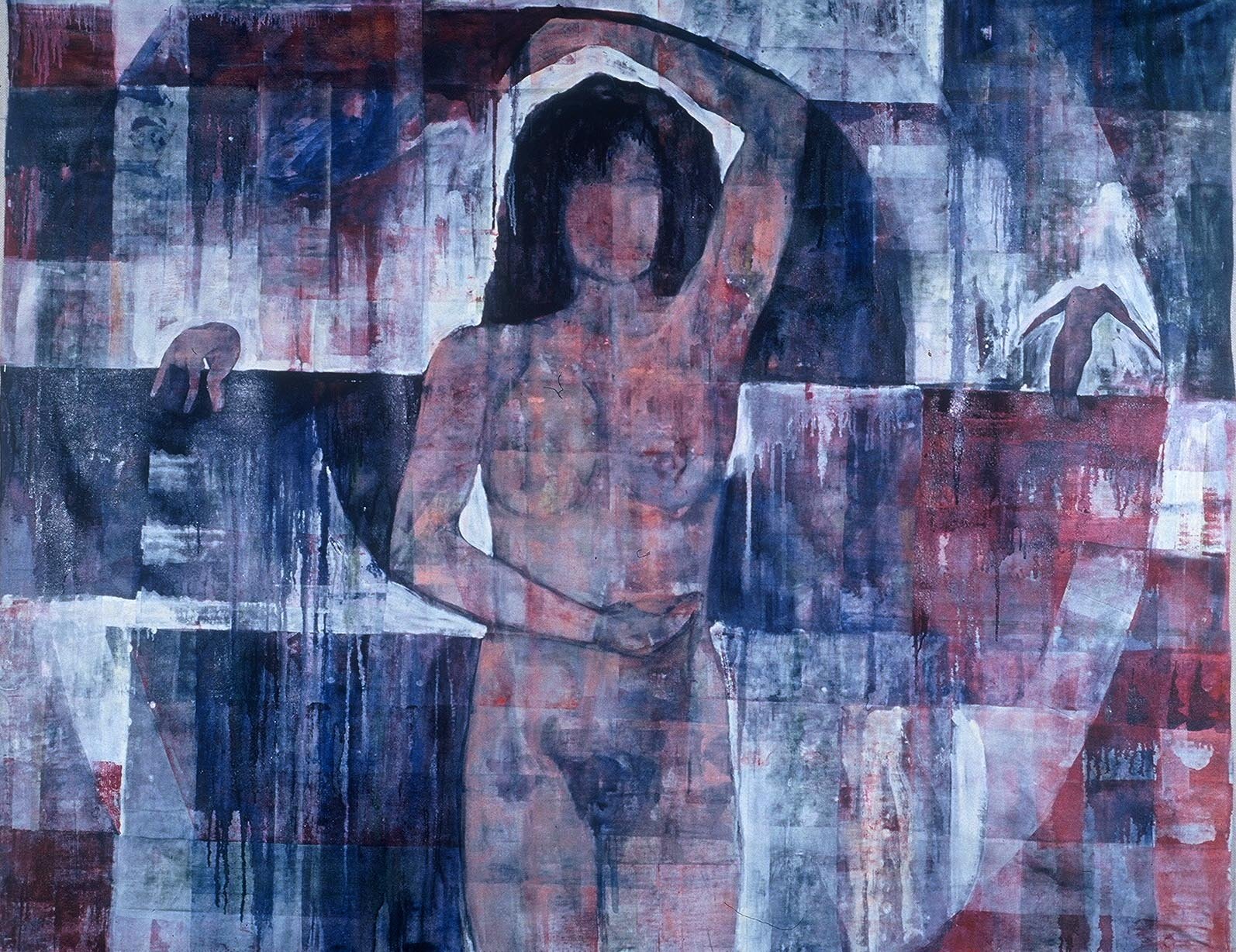

In the visual arts it manifests in the media I’ve explored, like monotyping—a place between painting and printmaking. Though I don’t have access to a press anymore, and I’m mostly focusing on figure painting, the techniques I used as a monotypist are still at play in my paintings, which consist of layering expressive textures of shape and color, usually very simple, nonlocal color, and then subtracting paint with rags. I’ve been told my work has a Modernist feel, and that makes sense, given my interest in not only the poetic but also artistic innovations of that time, namely Fauvism and Expressionism—cusp movements that sought to break with traditional representation in favor of bringing more attention to the act of painting and the medium’s expressive potential.

I’ve never verbalized it until now, but even the fact that I can’t seem to pull away from representing the nude is another kind of bardo fascination. The studio figure is a rather in-between creature, especially nude, and is fraught with a controversial subject/object history. Because they exist in a kind of mythic, aesthetic, erotic limbo, nude figures don’t seem to belong anywhere. This captivates me. There are all kinds of vulnerabilities and creativities, psychospiritual and geosexual political possibilities in not fully belonging somewhere or to someone. In the act of painting, I experience these figures as abstractions of such possibilities, abstractions of myself, even. There’s a breakdown in the subject/object dichotomy. It’s a very visceral experience.

That sounded very ivory tower and mystical all at once. Well done. What about poetry?

I would say most of my work falls in between free verse and form, which might mean that from either of those perspectives, I won’t make anyone completely happy. I like the freedom of not being married to meter and rhyme, but I flirt with both by employing tons of assonance and loose patterns of rhythm and line length. Some visual form, melody of sound and rhythm usually emerge, but never fully gel. And then there is the matter of content. Most of my work circles some hesitant nuptial between polarities: sacred and profane, self and other, male and female, gay and straight, infidelity and loyalty, natural and artificial, science and mysticism, presence and absence, independence and dependence, freedom and confinement. The list could go on.

Do you ever combine your poetry with your visual art?

Not often. Many years ago I wallpapered a gallery with collected and original writings. That pissed off a couple of my art professors. I’ve also done an oil self-portrait with shreds of my poetry collaged into it. And last year I gave a reading with two large abstract paintings as backdrops, but other than that, I haven’t explored it as much as I’d like to. Perhaps the marriage comes in bringing a visual sensibility to poetry, and a poetic sensibility to painting.

You’ve used a marriage metaphor three times now. What’s going on?

Hmm. I’m intrigued by figurative marriage—perhaps the ultimate metaphor for the natural state of things. I can see why people are so drawn to literal marriage, the urge to enact that state in a very concrete way. I admire people who do it well and feel compassion for those who struggle with it. I suppose the bardo principle also rules my relationships, my attractions to other human beings. I’m not sure how I feel about this, or if this is at all a good thing.

Why cultivate it then?

I’m more at ease in the between, and when I think I could settle in one place for long, I tend to slide out, or to at least want to very badly. Actually, I’m not so sure I am at ease being this way. Enlivened is perhaps the better word. Bardo places can be very uncomfortable in a world where staying put helps the gears turn more easily, but there is an irresistible power there. A creative power. I think the truth is we are all in between something or other. How aware we are of the fact, or how much we fight or embrace our tendencies toward extremes of solidity might be directly related to how much we suffer.

Don’t take this personally, but does TNB really understand what they are getting into by asking a Buddhist to interview herself?

Who is asking me this question?

Who is answering it?

Ah….hm.

Sneaky segue. And a little corny, I might add.

Oh! That was a spontaneous “ah,” I swear. But it just so happens that ah is the title of my first book, and you might want to ask me about it. Besides, Rosemerry suggested you ask what I am most afraid of when I think of people reading this interview, so we might as well get that out of the way while I’m shamelessly self-promoting my book: fear of being perceived as corny.

Hey, I’m supposed to ask the questions, not Rosemerry.

What’s the difference? We love her. She also suggested you ask me what I wish we would not talk about.

You are being controlling.

I’m just offering suggestions. So, do you want me to answer that one?

No.

Ok.

Can we start over here?

Always.

So, what do people need to know about ah?

Its genesis is largely described in the opening notes to the book, but I’m happy to explain a bit here. In 2010 I had begun studying a collection of poetic meditation instructions written by ancient Dzogchen masters of the Bön Buddhist tradition. By the summer of 2011, it occurred to me it would be interesting to attempt to write my own poetic reflections on this practice. So, basically, the poems that became ah were simply a prolonged exercise in using one mindfulness practice, poetry, to clarify another, Dzogchen. Or maybe it is the other way around.

I didn’t plan on arranging the poems into a book until Markiah Friedman of Liquid Light Press invited me to send him a manuscript after seeing me perform a couple of them on his Poet’s Co-op TV show. I live in a very conservative part of Colorado and hadn’t read them to anyone there yet. Reading the poems for Markiah and three cameras not far from Buddhist-friendly Boulder made me, um, bolder. I’m glad I took the risk. It turns out Liquid Light Press is dedicated to publishing poetry that explores realms of spiritual experience with an attention to craft. It’s a great venue for poetry that usually doesn’t have a place in more academically focused publications. Liquid Light Press is one of those in-between places I love.

Can you say something about Dzogchen?

Sure. The word itself means great perfection and is so simple, experiential and nonconceptual, it’s a little hard to explain. Practically speaking, it’s a kind of meditation practice whose purpose is to help us rest in what is called our natural mind. It is said our minds are naturally spacious and clear. But it’s hard to relax into this state without a little help. Hence the instructions. Hence the practice. It’s not about getting rid of thoughts, though. That’s impossible. It’s more about changing our relationship with the thoughts, emotions, words and images that run around in us. In practice, they might still gallop about at first, but we don’t ride off on them. Eventually they nestle down for a nap. When they stir, we gently notice. Without any effort on our part, the animals come and go, arise and dissolve, of their own accord, and we learn to rest in this subtle movement without judgment or nihilism. I’ve used a metaphor here, but promise me you’ll forget it. There’s room for everything in this place. I like to go there. I think most people might like to, regardless of their personal belief system or lack thereof.

Watch yourself, Sister Kellum.

That’s funny. I know with our Mormon upbringing you worry about people thinking you are trying to convert them or something, but you and I both know this isn’t about religion but sanity. Most of us are pretty busy-headed. Who doesn’t want a break from that? Everybody deserves some respite from, some perspective on, the entertaining tango of their own horseshit and glory no matter how they come by it. I’ve found that when I come back to the mundane world after a successful practice, creativity comes more spontaneously. Words flow. Crafting and revising is a joy. Though these aren’t the reasons I practice, I love these perks, and that’s how most of the ah poems were born. Not all of them are about being open and spacious (which is what ah, or the Tibetan letter a, means, by the way). Many of these poems are actually just my mind rustling words instead of resting in space.

Isn’t writing conceptually about something that is meant to be a nonconceptual experience kind of counterproductive?

Probably. The great irony of writing this book and then memorizing many of the poems for performance is that they have become obstacles to my meditation practice. Shortly after a performance, when I’m on the cushion, a few of the clearer poems prance around, proudly pontificating about my natural state, and then I miss out on the experience completely. The ego is so tricky. So, not taking these poems too seriously has become another layer of my practice. I’ve had to let them go, or stop riding off into the sunset on them, at least.

I thought you said you left behind organized religion. You sound pretty seriously involved with this Bön stuff.

I know. I don’t want to talk about that too much. Discussing my dedication to the Bön tradition always makes me a little nervous. And to be honest, having my book out there only compounds that feeling because I don’t want pegged as someone setting herself up as some kind of guru, on one hand, or as only a Bön poet, on the other. It’s a bardo book for me—not fully at home in the world of Buddhists or poets; though, it was a fine moment to share a few of these poems with my teacher and sangha at the end of September this year.

I should say here that most of my poems, outside of ah, are not about meditation practice at all, though it is true my poetry is driven by the undeniable need to bring awareness to my living. I’m not sure why I suddenly feel this urge to defend myself. I’m a word-addicted person who needs serious help with this fact. My head rarely shuts up. That’s a good reason to practice. Can we talk about something else now?

Sure. What?

I want to say that yesterday I raked leaves with my three big kids, ages 10, 13 and 18—two of them are my size now—and I was grumpy almost the whole time. We have two dogs, and doing poop patrol in the midst of brown leaves is the worst kind of Where’s Waldo. Sam, the youngest, helped me with this awful task without complaining. We wore plastic grocery sacks on our hands. My two oldest kids, without my guidance, figured out the coolest way to bag leaves quickly. Grey held two rakes parallel to his arms and scooped up leaves like the most efficient Edward Scissorhandsian boymachine (Sam asked, “Isn’t that a scary movie?” and Grey said, “No, I think you are confusing horror with horrible.”), while Sage used a five gallon bucket to repeatedly compress leaves in the garbage can. I took over when Sage had to leave for work. All told, there were 24 bags, and we finished in just a couple hours. I’m sore. I’m psyched my kids are so smart and helpful when they aren’t texting or Facebooking and playing Minecraft. I can’t believe these huge beings came out of me, talk to me, critique films, and help rake leaves. I admire their ability to inhabit both digital and analog worlds quite joyfully. They had me laughing by the end of the chore.

Do you write about them much?

Sometimes. I’ve always loved how Robert Hass writes about his kids. One poem in Human Wishes, the first book of his I ever owned, reveals a moment when his son, Leif, tells him, “Dad,[…] I’m not taking any more/ of this tyrannical bullshit.” And when Hass responds by reading a line from Chia Ya, the boy adds, “And another thing, don’t lay/ your Buddhist trips on me.” I hope my work is as honest as that. I have collected almost everything he’s written. Our styles are quite different, but I adore Hass, his catalogues of observation. He isn’t corny at all. His long lines have carried on a low conversation with what is hardest in me for many years. There is a natural, honest rhythm in them that I’m always aiming for. In his essay, “Rhythm and Making,” he tells us, “Because rhythm has direct access to the unconscious, because it can hypnotize us, enter our bodies and make us move, it is a power. And power is always political. That is why rhythm is always revolutionary ground.” Mmm. Such words inspire gratitude for all the poets and song writers whose rhythms have revolved and evolved me over the years: Hass, of course, and Eliot, Roethke, Stevens, Whitman, Ginsberg, Chris Whitley, Ani Difranco, Greg Brown, and a generous and gifted family of Colorado poets who play at words with me.

One more thing about Hass. In the mid-90s, a guy in a local Fort Collins bookstore helped me locate him on the shelf. He informed me he didn’t like Hass’s work; it was too privileged, not political enough. As a graduate student at the time, I thought there must be something to what he said.

I bought Human Wishes anyway.